Funding The Best Water Entrepreneurs in the World

Finding value where others don’t, essential advices for Water Tech Founders, the importance of Marketing and Sales, and why being early isn’t always right.

This episode feels like placing a key puzzle piece that connects four others, suddenly revealing a much bigger part of the picture.

Space reserved for future sponsors.

After a few months of learning from later-stage investment perspectives, more mature and medium-term, now we’re gaining insight from the very early stage.

So I’m really grateful and proud of having Tom Ferguson from Burnt Island Ventures (BIV from now on) in The Water MBA so we could talk about water, investment, and much more.

I also asked Tom: if I wanted to move to New York and work at firms like BIV in, say, five-ten years, what should I do in the meantime to be ready when the time comes?

Curiously, two of his recommendations actually became a major inspiration back in 2022 for the creation and shape of The Water MBA as it exists today. I’ll explain that part later.

Who’s Tom and BIV?

Tom Ferguson, a British person residing in Brooklyn and Managing Partner of Burnt Island Ventures, offered insights into the mechanics and mindset required for success in the early-stage Water Tech investment space.

His background includes 15 years in water—specializing since 2015 by running the accelerator at ImagineH2O—explained that BIV was founded in 2020 because no one was deploying capital systematically at the seed stage in water, which he viewed as insane from both a returns and a climate change perspective.

BIV has since grown, closing a $50 million second fund and working to build the comprehensive water investment platform they wished existed previously.

The Strategy of Early-Stage Investment

BIV focuses on the very early stage of the water innovation curve.

Tom explained that this focus is primarily driven by the prospect of returns.

Operating early allows BIV to acquire company shares for much less than they would be worth when the company is more developed.

This approach relies on a specialized, differentiated ability to evaluate companies based on what may seem like less evidence to others.

Their expertise—honed over five and a half years at IH2O and now five years running BIV—allows them to understand the mechanisms necessary for company development and, crucially, how to “stay out of trouble” at the earliest stages.

Although BIV began focused on seed capital, they have expanded into Series B investment to help fill gaps in the water investment structure, recognizing that Series A is reasonably well represented by specialists, but growth capital at Series B was lacking.

Tom described the early stages as inherently difficult, comparing the work to trying to control entropy, taking chaos and corralling it into order with minimal resources.

BIV maintains a sector-agnostic approach to investment.

While trends like leak detection, high replacement, or data center cooling may look obvious, Tom believes it is crucial to have a prepared mind for everything in water, from utility billing to agricultural runoff reuse, and the generalized paradigm of recycling, reuse, and full circularity.

Ultimately, BIV is judged by its returns, meaning decisions are rooted in the expected value relative to the entry price.

Investing in highly attractive fields often comes with a “giant price tag,” making it difficult to secure serious returns.

As an illustration, obtaining a 30X return requires a $1.5 billion exit if investing at a $50 million post-money valuation, but only a $150 million exit if entering at a $5 million post-money valuation.

Therefore, BIV must remain open to “opportunistic entry points” and ideas that might look “quite weird looking”.

Regarding portfolio management, BIV’s strategy is to “concentrate early and then we try and defend our stake”.

Essential Advice for Water Tech Founders

Tom provided sharp advice for founders struggling to secure capital, noting that the volume of effort required is often underestimated.

Understand the Competition

Founders often limit their competitive frame to immediate product rivals. When seeking capital, however, the competition is literally everybody (other water companies, generalized climate ventures, or even companies in Fintech, AI, or crypto).

BIV has seen nearly 3,000 companies but invested in only 34, underscoring how high the bar is.

Master the Argument

Money is available, but founders must win it. This requires building a compelling argument backed by evidence, often necessitating countless iterations of the story and data.

The ability to communicate effectively in the room is critical, as investors are underwriting the founder’s capacity to raise money in future rounds.

Tom suggested that developing this argument is like playing jazz: mastering the basic structure and then playing jazz by providing an elevated and differentiated argument.

Do Not Outsource CEO Duties

The founder’s core job is threefold: hire amazing people, set the direction of their activities, and ensure the company is funded.

Outsourcing the capital-raising component—for example, relying on bankers or consultants to make the arguments—is seen as a “not good idea” and is not a compelling position for BIV.

Structural Gaps in the Water Business

Tom identified key areas where the water business, as a whole, needs significant improvement, starting with marketing.

Yes, marketing!

He clarified that marketing is deeply misunderstood; it is not just about having a website or conference swag.

Marketing’s true role is to understand where the sales effort should go and smooth the path for the sales team to generate cash.

The industry needs an influx of serious talent that understands how to market properly to idiosyncratic verticals, such as utilities or treatment teams at semiconductor plants.

Secondly, sales is an area of high respect but also common mistakes.

The biggest mistake founders make is hiring sales leaders too early, or hiring ones who are inflexible.

These leaders often try to impose an outdated “playbook” rather than having the humility to learn the company’s existing logic and layer on useful expertise.

The Role of Regulation in Investment

I asked him whether, based on what we’ve seen in the past, regulation can drive innovation, and whether it makes sense to anticipate those shifts and position yourself in the right place before the regulatory changes actually arrive.

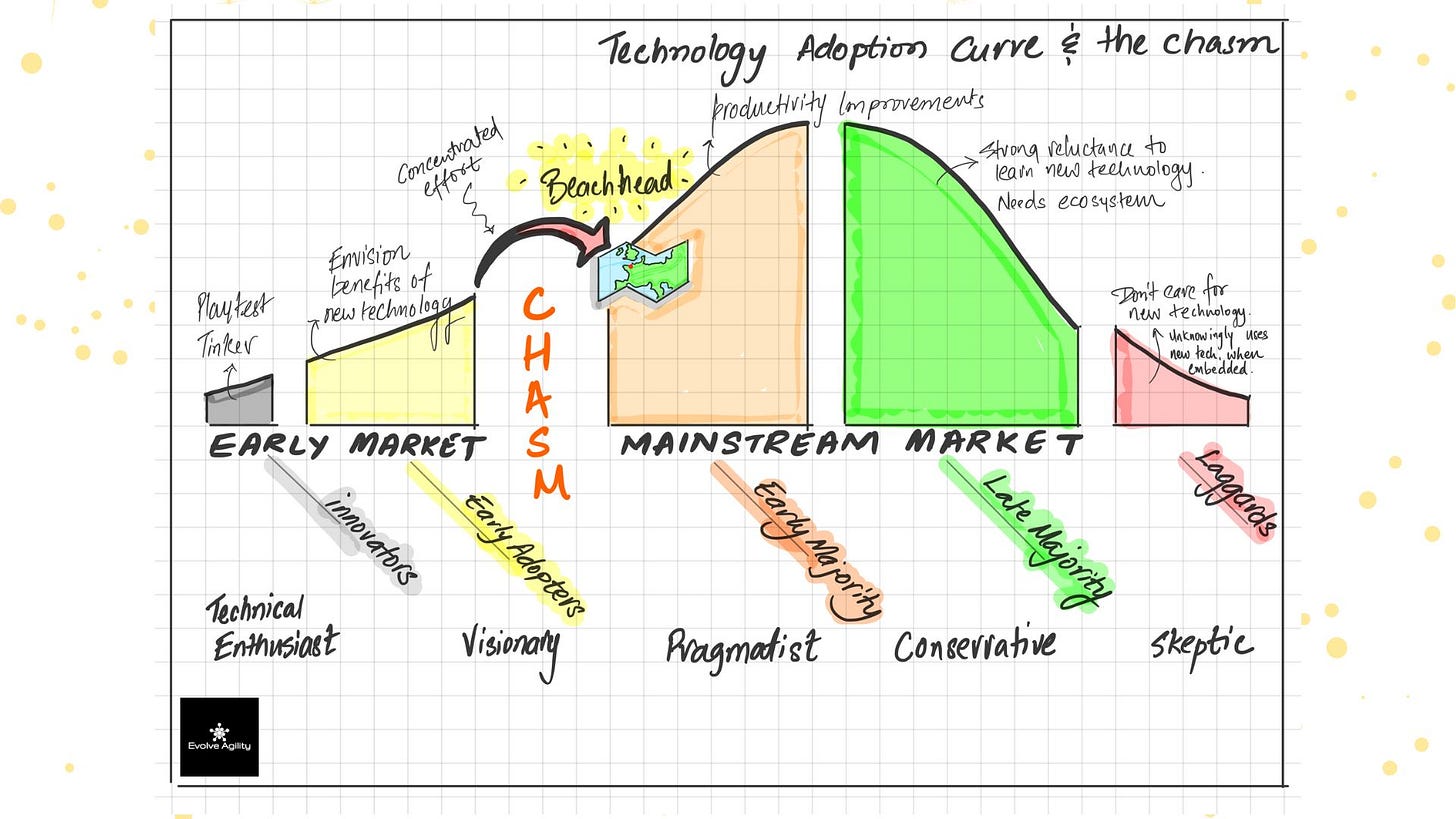

A significant lesson regarding market timing is that “in investing being early is the same as being wrong”.

Tom stated that trying to time regulation is generally a “fool’s errand,” as political shifts can change the regulatory environment quickly.

Instead of predicating investment decisions on future regulatory assistance (like tax credits, grants, or new rules), BIV underwrites companies that make abundant sense based on current customer incentives, degree of pain, and unit economics.

The company must be able to grow big on its own logic without regulatory help.

If regulation does arrive and provides a boost, that is simply a benefit that supercharges success, not the foundation of the value proposition.

Recommended Resources

As I wrote before, I asked Tom: if I wanted to move to New York and work at firms like BIV in, say, five-ten years, what should I do in the meantime to be ready when the time comes?

Tom emphasized that continuous learning and growth require input beyond technical water aspects.

He provided several key resource recommendations to help professionals understand the architecture of poor decision-making and the logic of start-ups:

Poor Charlie’s Almanack by Peter Kaufman, a compendium of Charlie Munger’s speeches, particularly the one on “The Psychology of Human Misjudgment”.

Paul Graham’s essays, though readers must have the discernment to adapt generalized startup advice to the specifics of the water sector.

Understanding flywheels, which are self-reinforcing business benefits that act as moats beyond IP (intellectual property). They protect a business from competitors in ways that go beyond just IP.

The Water MBA Connection

Now let me explain how this latest resonated with me when I was laying the foundations for my “I have no idea what I want to do with my life” phase back in 2022.

I didn’t know what kind of “founder” I was going to become, or even if I would become one at all.

Around that time, I discovered Paul Graham’s essays. Click and prepare yourself to travel in time!

Paul Graham—if you’re not familiar—is a programmer, writer, and co-founder of Y Combinator, one of the most influential startup accelerators in the world.

His essays, written over many years, are like an ongoing public journal: reflections, advice, observations, stories… incredibly thoughtful and unusually honest.

I found this format exceptionally original. And it became one of the inspirations behind the current structure of The Water MBA: writing and sharing regularly what we learn. I realised how powerful it can be to accumulate short essays over time—how the impact compounds.

That leads to the second inspiration: the flywheel.

A flywheel in business is a self-reinforcing cycle where each action strengthens the next, making the system harder to stop or replicate. And because it is based on process, feedback loops, culture, data, and execution, not patents, it becomes a non-IP competitive moat.

Because even if someone copies your product, they can’t quickly copy the momentum, the ecosystem, the accumulated data, or the compounding benefits that your flywheel has built over time.

Once I understood the flywheel concept, it became clear that every step or effort should reinforce the next. Each action should add value, unlock new opportunities, and feed a continuous cycle of review, refinement, and data accumulation.

This has been my working mindset for the past three years. Not only in building The Water MBA, but also in my corporate job: every project, every experience must consolidate and strengthen the next one.

I often see professionals in our industry who don’t really progress—who don’t perform better, aren’t more productive, and feel stuck—because they focus solely on “completing tasks.”

They get the work done, but they don’t extract the lesson from the work.

Experience does not come from the task itself; it comes from reflecting on the task. If you don’t give yourself time to think about what you did and how it could improve tomorrow, then you’re not really growing.

Well, I hope you enjoyed the reading. See you next week!