Navigating Water Politics

The Paradox of Water: when scarcity drives innovation and abundance breeds crisis. Why political will and governance define global water security.

Today, I wanted to learn more about an important piece of the puzzle of our water business: politics.

Today’s sponsored edition is from Agru.

I’m attending and moderating a few panels in Desalination Technology Expo at Valencia, and they will be there too (here the proof). So I suggest meeting their specialists for first-hand insights into thermoplastic solutions tailored to seawater desalination: PE 100-RC intake and outfall pipelines; permeate and brine piping; chemical dosing and storage systems (PP, PVDF, ECTFE); and concrete protection liners for tanks and basins.

I also recommend you to talk to them about the upgrading and retrofitting existing plants and facilities. I’m perfectly aware of Operators replacing systems due to wrong designs and low quality material, for instance in the HDPE permeate at RO Racks.

Desalination Technology Expo / 04 – 06 November 2025 / Booth no° 1010, Feria València, Spain

Our guest, Mishelle Mejia, provided a highly insightful exploration into the complex world of global water politics, utilizing Mishelle’s unique perspective spanning from water-abundant Latin America to water-scarce Israel.

The discussion highlighted the urgency of treating water as a strategic shared resource and underscored the critical roles of governance, diplomacy, and political will in effective water management.

The Paradox of Scarcity and Innovation

A central theme of the conversation was the contrast between regions facing scarcity and those blessed with abundance.

Mishelle noted the paradox of her experience growing up in water-rich Honduras, where supply was inconsistent, compared to arid Israel, which provides 24/7 water for 10 million people.

This disparity emphasizes that the core issue is not necessarily a lack of water, but a failure of governance.

Israel serves as a compelling case study where scarcity drives innovation and cooperation.

Despite natural aridity, Israel achieved water security through technological responses, robust policy frameworks, and the establishment of a national water grid.

Critically, Israel manages its entire water system (desalination, wells, sewage) under one depoliticized authority, ensuring that decisions are data-driven and focused on the long term. In this system, the priority is clear: the population comes first.

Consequently, 95% of treated wastewater is reused for agriculture, conserving potable water for the populace.

The conversation extended this success story to regional diplomacy through the case of Israel and Jordan.

Their 1994 Peace Treaty includes a vital water annex, establishing annual negotiated water transfers.

This reliance on water supply for regional stability demonstrates that water is a crucial tool for peace and stability, compelling Israel to continually invest in desalination and technology to maintain sufficient supply for both nations.

The Water Bridge Between Jordan and Israel

Back in 1994, when Jordan and Israel signed their historic peace treaty, one of its most tangible and lasting achievements wasn’t about borders or politics, it was about water.

The treaty included a detailed annex, simply titled “Water-Related Matters.”

It was a technical document, yes, but behind it lay that in this arid region, water is life, and cooperation over it could be the foundation for peace.

Under this agreement, both nations committed to share the Yarmouk and Jordan Rivers, manage groundwater together, and create mechanisms for joint decision-making.

Jordan, facing chronic shortages, was guaranteed a transfer of 50 million cubic meters (MCM) of water annually from Israel’s system — a critical supply for agriculture and urban needs.

In return, Jordan agreed to provide Israel 10 MCM of water from the Yarmouk River during the summer months, essentially a seasonal swap to balance the flow.

Beyond these allocations, the two countries established a Joint Water Committee, tasked with monitoring water quality, managing infrastructure, and addressing disputes.

Both sides recognized that cooperation wasn’t just about dividing water, but about creating more of it through technology and smart management.

Over time, this spirit of collaboration evolved. One of the most ambitious ideas (finally abandoned I think) born from it was the Red Sea–Dead Sea Project, a proposal to desalinate seawater from the Red Sea near Aqaba, share the freshwater between the two nations, and channel the remaining brine north to the Dead Sea to help counter its alarming decline.

And more recently, in 2021, a remarkable new deal extended this partnership into a new era, water-for-energy agreement, often called the “Prosperity Green and Blue” project: Jordan would supply 600 MW solar energy to Israel, while Israel would provide 200 MCM of desalinated water annually to Jordan — four times the volume agreed upon in 1994.

It’s a new kind of exchange: sun for water, energy for life.

Around the world we may find another cases of quiet diplomacy of engineers, hydrologists, and farmers who keep the water flowing every day. I’ll keep bringing more cases to the table.

The Challenges of Abundance and Mismanagement

The situation in Latin America presents the opposite challenge:

Abundance undermined by inadequate governance.

Again, remember this was exactly stated by our guest Santiago Gomez from the World Youth Movement leading in Latin American and Caribbean.

Although the region has high average rainfall and major river basins, it struggles with pollution, unequal access, and severe infrastructure gaps.

Mishelle noted that politicians often use water as a control tool, leading to short-term political cycles replacing long-term infrastructure projects.

Many essential facilities, such as wastewater treatment plants, collapse because they require consistent flow, which is impossible when older drinking water infrastructure cannot handle growing populations, resulting in inconsistent 24/7 supply.

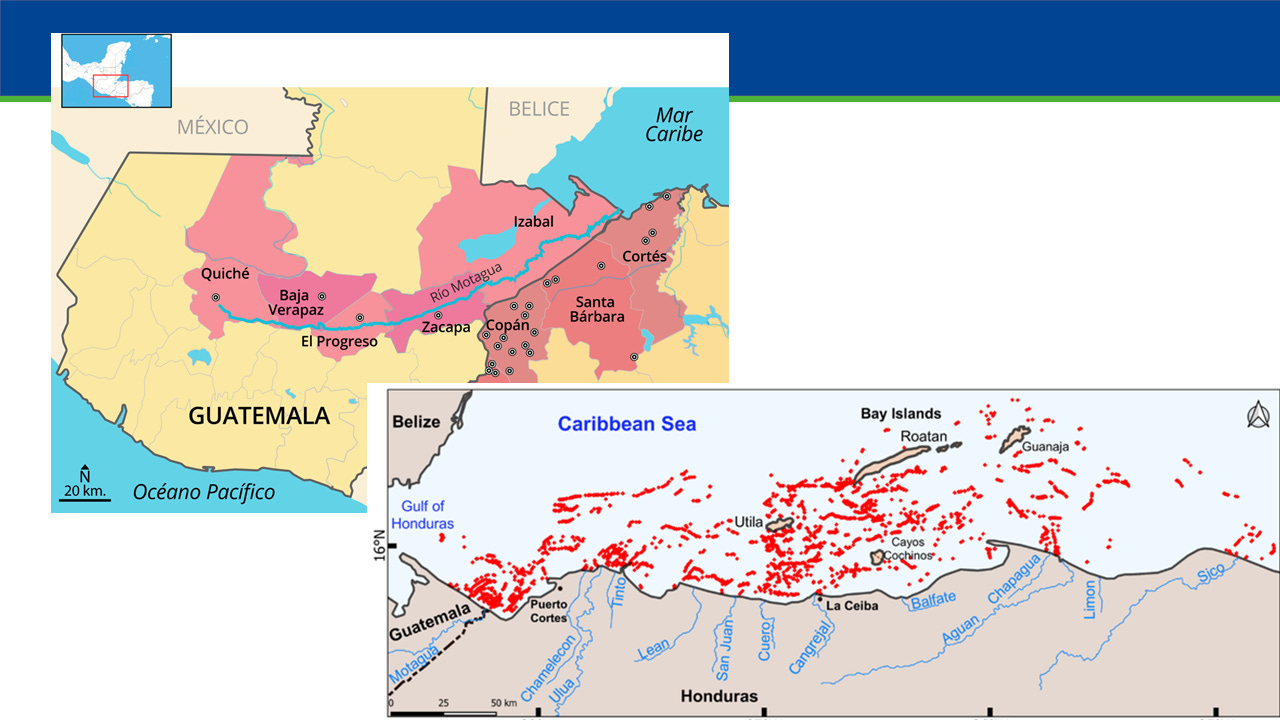

This governance weakness can quickly transform a natural resource into a source of conflict, as exemplified by the Motagua River Basin shared by Honduras and Guatemala.

This transboundary issue is characterized not by scarcity, but by a massive pollution crisis.

The Motagua River is considered one of the world’s most polluted due to illegal dumping, untreated sewage, and irresponsible waste management, especially during the rainy season when flash floods carry vast quantities of plastic waste downstream.

This pollution severely damages Caribbean marine ecosystems and inundates beaches in neighboring Honduras, leading to significant economic costs and diplomatic tension.

Solutions being deployed include diplomatic coordination and high-tech interceptor barricades to capture the waste before it reaches the sea.

You may watch this interesting video available in Youtube.

Anecdote at the Rethinking Water Conference

At the end of my presentation at Rethinking Water in New York, my final slides included a few quick “knowledge tests”, small questions meant to remind the audience how much we all still have to learn.

Interestingly, one of those questions was about the most polluted river on Earth.

After the talk, someone from Guatemala approached me.

He told me he firmly believes that education and knowledge are essential to driving real change in his country.

Politicians

I often feel that politicians and governance are among the biggest barriers to effective water management in many countries.

In places where water challenges are most severe, solutions rarely come quickly.

You can’t change cultural behaviors, institutional inertia, or entrenched power structures overnight.

Of course, there are good politicians and bad ones.

Some seem content with the status quo — driven by power, comfort, or self-interest, showing little concern for the public good, and often lacking even basic knowledge about water management.

But I also believe there are good politicians — people who genuinely want to make better decisions but might simply need more education, perspective, or guidance.

And that’s where we can help. Let’s find those people, support them, and empower them with the knowledge they need.

Spanish Politics

We also discussed on internal water politics in Spain, which faces its own challenge of strong regional disparities between the wetter north and the arid southeast.

Historical attempts at inter-basin transfers have met political and social resistance, demonstrating the difficulty of balancing regional economic interests with solidarity and environmental sustainability.

Areas like Murcia (in the arid southeast) have become centers for innovation in water resilience, prioritizing wastewater reuse to support the region’s vital food export industry.

Remember our episode with Dario Salinas about water geopolitics in Spain.

Some Takeaways

You can drive home these takeaways:

Political Will: This is the most critical ingredient needed to enable transfers, redistribution, and lasting change. As our friend Walid Khoury said in his episode, this is the elephant in the room, and there is no water scarcity when there is political will.

Governance and Corruption: Abundance requires strong governance to prevent pollution and waste, while systems must be protected from debilitating corruption.

Education: Public awareness and education are fundamental, starting from a young age, to ensure citizens understand the water cycle and advocate for their right to safe water and sanitation. But also educating those already in our industry.