How Singapore and China are Redefining Water Resilience

From Singapore’s drive for total water independence to China’s river-chief accountability and water-intensity metrics, the East is providing a masterclass in institutional agility and long-term vision

I wanted this conversation because, in the West, we often feel stuck in a cycle of short-term thinking and aging infrastructure.

I wanted to understand how places like Singapore and China, despite their vastly different scales, manage to plan decades ahead and treat water as a non-negotiable priority for national security.

Space reserved for future sponsors

It is a true honor to welcome Cecilia Tortajada to The Water MBA, her background speaks for itself:

Honorary Professor at School of Social and Environmental Sustainability, University of Glasgow

Visiting Professor, School of Water and Environment, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China

Distinguished Visiting Professor, Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi, India

and much more—well worth exploring on her LinkedIn profile.

She had to choose between sharing her knowledge at Harvard or The Water MBA, and we’re proud she chose us :)

But beyond her stature as a world-renowned expert in water policy, Cecilia is a great professional, yes, but she is an even better human being, warm, insightful, and genuinely passionate about the social impact of water.

The context: why long-term planning is rare (but necessary)

In many parts of the world, water management is reactive.

We respond to the latest drought or the most recent flood, but rarely do we see policy that spans 50 years.

This conversation connects to the fundamental challenge of institutional resilience.

Whether it’s Singapore’s lack of natural resources or China’s struggle with historic pollution, these regions have moved past “managing a crisis” toward “designing a future.”

Singapore’s “Four Taps” and the drive for independence

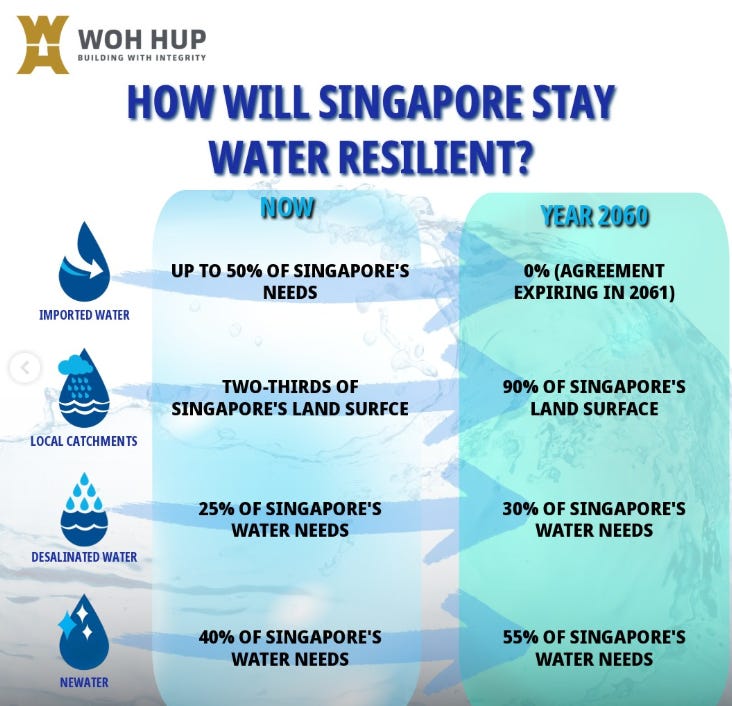

Singapore is famous for its “Four Taps” strategy: local catchment, imported water, desalination, and NEWater (recycled high-grade reclaimed water).

Cecilia highlighted that it is a political action born from necessity.

The most striking takeaway for me was the timeline. Singapore knows its water agreement with Malaysia expires in 2061.

Instead of waiting for a deadline or hoping for a renewal, they have spent the last 50 years investing in R&D to ensure they are self-sufficient long before that date.

It’s a masterclass in sovereignty through technology. They are buying water and their own future security.

As you can see in the picture above, NEWater (recycled/reused water) is going to have a major role.

The Power of “whole-of-government” coherence

In Singapore, agencies don’t work in silos.

This is a concept Cecilia calls the “whole-of-government” approach.

If a new industrial district is planned, the National Water Agency (PUB) is already at the table, building the infrastructure before the first factory even breaks ground.

Cecilia noted that this “one-layer government” approach ensures that water policy isn’t just about pipes, it’s about energy, land use, and economic growth.

In many of our home countries, different departments often fight over the same dollar or the same plot of land.

In Singapore, the goal is always the same: keep the island viable.

This level of institutional alignment is something we desperately need to replicate. Though I’m not very confident of achieving so nowadays…

China’s River Chief System: accountability at the top

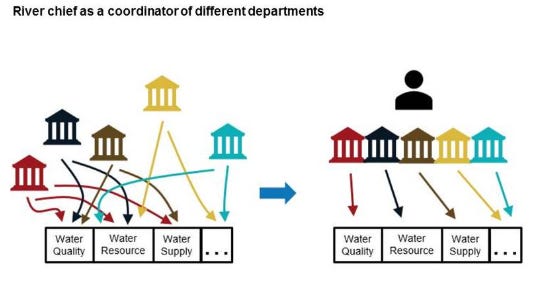

Moving to China, because Cecilia has also a great experience in this country, we actually recorded our conversation after her journey to China for a few weeks, I discussed the “River Chief” system, which was one of my favourite learning outcomes.

In this system, high-ranking officials are personally responsible for the water quality of a specific stretch of a river.

If the water quality doesn’t improve or if pollution persists, those officials face serious consequences, they can be demoted or lose their jobs.

This moves water management from a vague “departmental responsibility” to a personal career incentive.

It’s a blunt but highly effective way to ensure that national environmental targets actually get implemented at the local level.

It turns out that when a leader’s job depends on a clean river, the river gets cleaned very quickly.

I imagine myself being responsible for the stretch of river that goes through my neighbourhood or region, and it’s mind-blowing!

Water Intensity: the metric for success

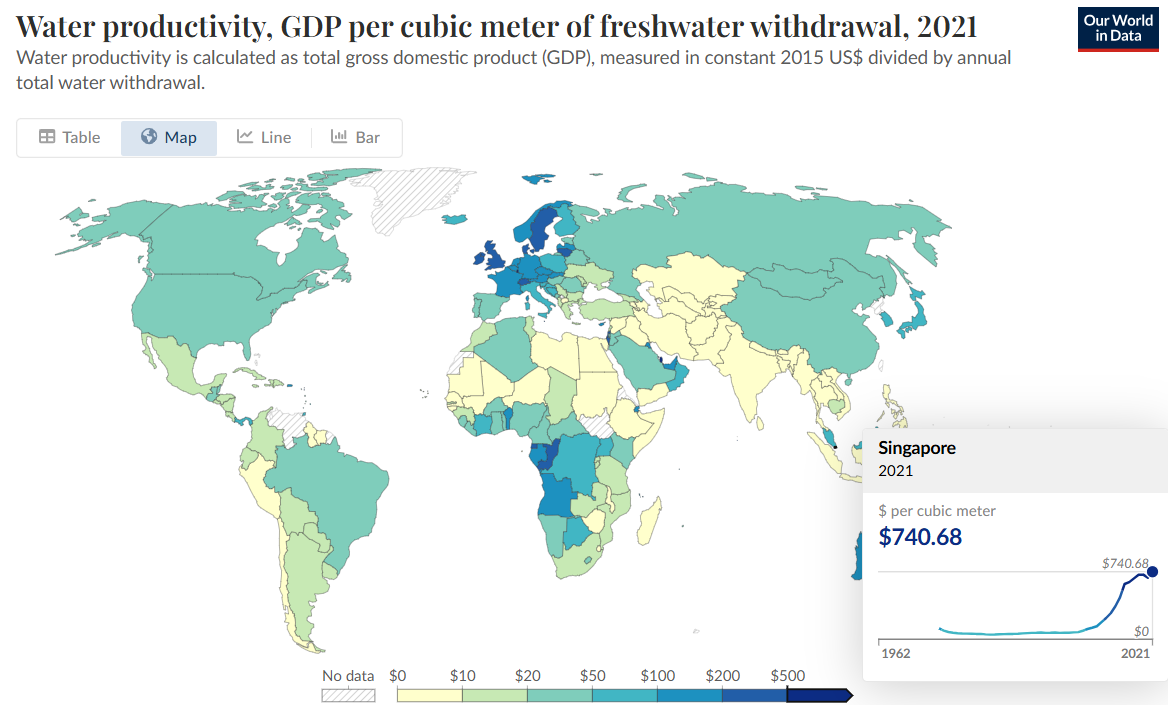

We often talk about water scarcity, but Cecilia introduced a more sophisticated concept that I was not aware yet:

Water intensity: This measures the relation between water consumption and GDP.

China and Singapore use this to measure efficiency. If your GDP is growing but your water use is growing faster, you have a structural problem.

By decoupling economic growth from water consumption, these countries are proving that you can be a global industrial powerhouse without draining your natural capital.

It’s a shift from seeing water as a “free resource” to seeing it as a “strategic asset” that must be used with maximum precision.

I loved this metric to be honest. If you are curious to analyse the details and data from different countries, here an interactive map.

Managing floods with data, not just concrete

We touched on the terrifying reality of floods.

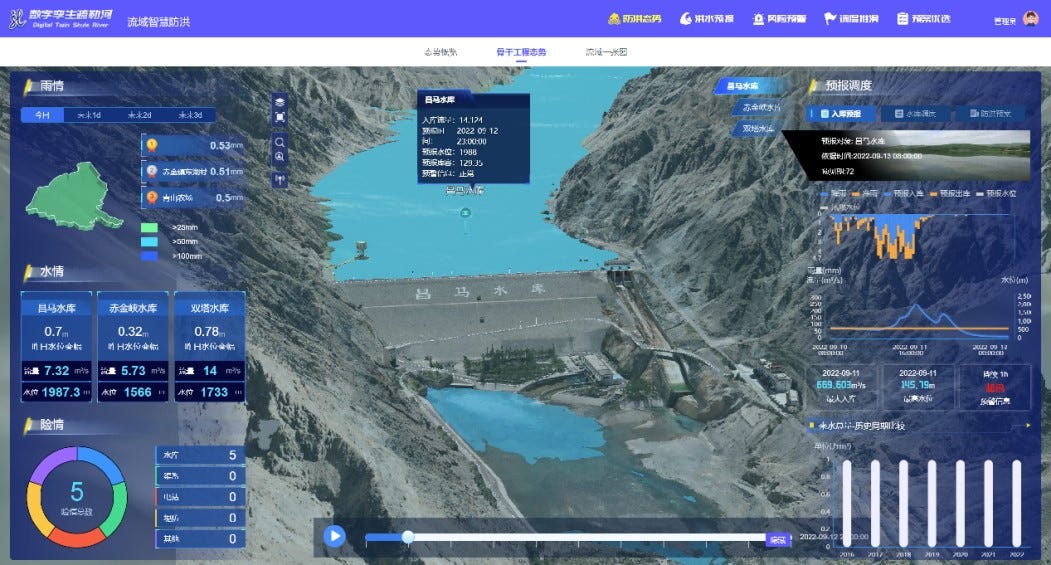

Cecilia pointed out that China is heavily investing in Digital Twins, virtual replicas of river systems like the Yellow River.

These models allow them to forecast floods days in advance with high accuracy.

The lesson is about communication. Using that data to tell people when to evacuate, when to close schools, and how to stay safe is just as important as the dam itself.

In China, this information flows from the digital model directly to the citizen’s phone.

Technology is only useful if it leads to better, faster decision-making on the ground to save lives.

The role of large-scale infrastructure and hydropower

A particularly interesting part of our talk was China’s stance on dams and reservoirs.

While many Western countries are debating the removal of dams for environmental reasons (it touches my heart to be honest as this is my fav infrastructure), China is moving in the opposite direction.

They see large-scale storage as a fundamental tool for climate adaptation. It is considered actually a “green” infrastructure.

Cecilia explained that for a population of over a billion, you simply cannot manage the volatility of the water cycle without significant storage capacity.

This infrastructure serves a dual purpose: it provides a buffer against drought and generates massive amounts of hydropower (the oldest and best renewable energy you can find)

As China aims for Net Zero, hydropower is a key pillar of their energy transition.

They are proving that you can integrate massive infrastructure with sophisticated sensors to manage an entire subcontinent’s energy and water needs simultaneously.

Policy as a living document, not a static goal

Perhaps the most underrated lesson from the East is how they handle policy.

In the West, we often pass a law and consider the job done. In Singapore and China, policy is treated as a “work in progress.”

Cecilia noted that they set 50-year visions, but they break them down into 10-year and 5-year plans that are constantly revised.

They use “foresight exercises” to scan the world for new risks, like a sudden change in sea levels or a breakthrough in desalination energy efficiency.

They are not afraid to change course if the data changes.

This institutional agility allows them to stay ahead of the curve rather than constantly playing catch-up with the climate.

My reflection

After talking with Cecilia, I’m left thinking about the “Trust Gap.”

In Singapore, people drink from the tap and support water recycling because they trust the government’s transparency.

In China, officials protect rivers because their careers depend on it.

In our own regions, do we have that same level of accountability? Are we measuring our success by how many pipes we lay, or by how “water-intense” our economy is?

We often blame a lack of money for our water woes, but as Cecilia showed us, the real deficit is often in planning and political courage.

Water is the vehicle through which we see the development and health of an entire society.

If we want to build a resilient future, we might need to start looking East for the blueprint.

See you next week and thanks for reading, watching and engaging!