ACWA Power and Public–Private Partnerships.

A deep dive into the Saudi water sector reveals a powerful, exportable model for public-private partnerships that is already going global.

Today’s episode is an important one. It lays the foundation for concepts we need to understand before diving into upcoming business cases.

We hear “PPP” (Public–Private Partnership) everywhere — more private participation, shared risks, unlocking finance, …

But here’s the thing: most people don’t actually know how a PPP really works.

This edition is proudly sponsored by… Circle of Fifths Advisory😊

One of my best professional stages came “working and competing” alongside my friend Rani Abdallah. I learned so much during that time, he’s the kind of professional you always want by your side, someone who pushes you to bring out the best in every decision. And now, he has taken all that expertise, passion, and drive to create his own firm: Circle of Fifths Advisory.

Based in Canada, they bring sharp insights into contract and claims management, business transformation with AI, M&A support, bid management, and commercial program leadership. But what truly sets them apart is their holistic vision. Truly outstanding in both their work and the depth of connections they’ve built within our industry, genuinely impressive.

I can personally vouch for the quality and integrity behind. If you want a partner to unlock real growth, they are the one.

And if it’s such a beneficial model, why isn’t it implemented more often?

To answer that, we’ll look at what I believe has become a global reference in our industry: the Saudi model, developed and refined over the past two decades.

At the center of this story stands ACWA Power, a company that mastered PPPs in practice and scaled them across water and energy markets worldwide.

This episode belongs to the channel Business Case Studies series.

There’s no guest this time, although I did try inviting Marco Arcelli, ACWA Power’s CEO (my messages probably got lost in his understandably busy inbox!).

The power of a business case in understanding PPPs

Public–Private Partnerships often look like abstract acronyms, full of legal and financial jargon.

But to understand them, nothing beats a real-world business case.

ACWA Power shows us how PPPs function in practice: shifting execution and operational risks to the private sector, while governments focus on service provision, regulation, and long-term planning.

The company’s success demonstrates that the contract model itself — the details of ownership, risk allocation, and off-take agreements — is what determines whether investors and lenders step in.

This is the framework we need in order to see PPPs not just as policy buzzwords but as actual engines of infrastructure.

A brief history of the saudi water market & its key players

Since 2002, the Saudi water market has transformed dramatically, opening the door to private participation. Key entities as explained in the episode:

SWCC (Saline Water Conversion Corporation): the state-owned backbone of Saudi desalination since 1974. Now transformed to SWA (Saudi Water Authority). Why? The episode explains clearly the strategy.

NWC (National Water Company): managing the water cycle and distribution networks to end-users.

SWPC (Saudi Water Partnership Company): the main offtaker for desalination plants and big-scale wwtp’s, signing long-term contracts and ensuring stable revenues for private operators like ACWA Power.

In 2004, ACWA Power was born through a joint venture.

Backed by the Public Investment Fund (PIF), it quickly became the face of Saudi Arabia’s new model for PPPs in water and power.

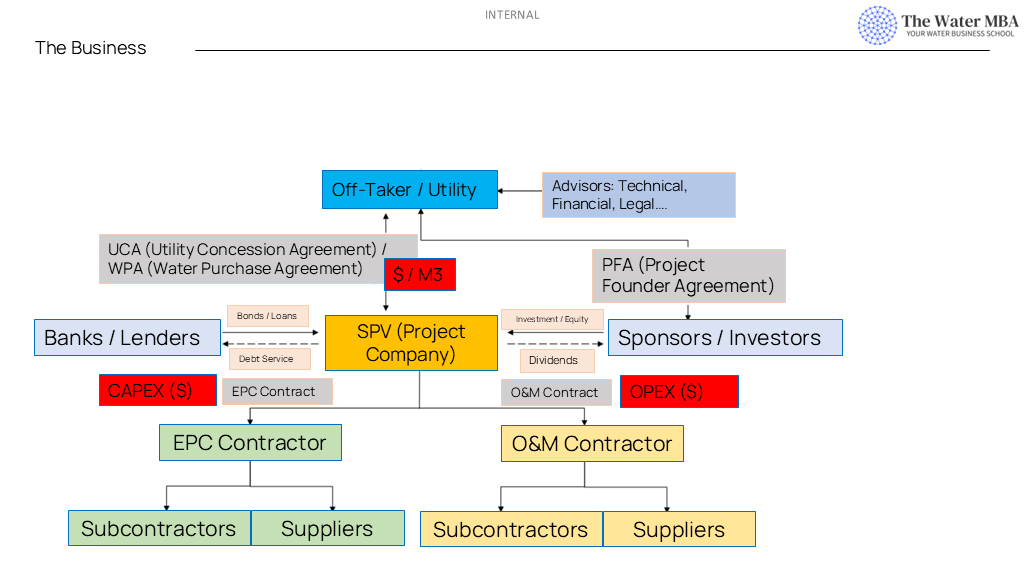

The PPP diagram — understanding the key relationships

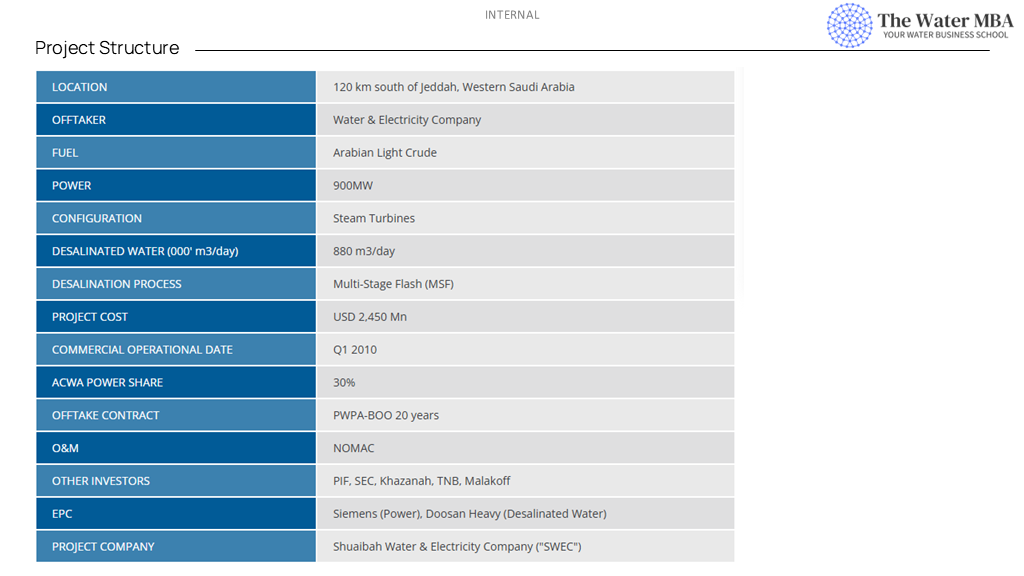

The heart of a PPP is the Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), a project company set up for each plant. The SPV shields risks and brings together all the key actors:

Investors/Sponsors: ACWA Power and partners putting in equity.

Lenders: banks financing the bulk of the project, secured by long-term contracts.

Offtaker (SWPC): guaranteeing demand via a Water or Power Purchase Agreement.

EPC Contractors: designing and building the plant.

O&M Contractor: operating and maintaining the plant — often ACWA Power’s own subsidiary, NOMAC.

Understanding this structure is the key to understanding how PPPs de-risk and attract billions in capital.

BOO vs. BOT vs. BOOT

Contract choice defines everything. ACWA Power applies mostly BOO.

BOO (Build–Own–Operate): private ownership for the long term (common in Saudi & UAE).

BOT (Build–Operate–Transfer): ownership passes back to the government after 20–25 years.

BOOT (Build–Own–Operate–Transfer): a hybrid model, with temporary private ownership.

Governments may prefer BOT or BOOT when they want to retain ultimate control (usual in highways for instance...)

So here’s the point: why does a public entity want to own an asset?

The answer is simple—they do not want to OWN the asset, they main priority is service assurance.

Their main objective is to guarantee reliable service, which in this context means securing 20, 30, or even 35 years of uninterrupted operation.

But to be honest, it depends on the country and the culture.

I’ve heard in some events that, to give confidence to the public side, the fact that they will eventually own the infrastructure can help in certain cases.

So, I think this is a topic that can be widely discussed.

The primary reason the Build-Own-Operate (BOO) model is more attractive is that it allows for indefinite private ownership of the utility asset.

This long-term ownership is a key advantage for private investors, like ACWA Power, for several reasons:

Long-Term Revenue Stream: Owning the asset means the private company can operate it for its entire useful life, not just for a fixed contract period of 20-25 years as in BOT or BOOT models. This provides a continuous and stable revenue stream for a much longer duration.

No Transfer Obligation: Unlike BOT or BOOT models, there is no requirement to transfer the asset back to the government at the end of the contract term. This eliminates the complexities and potential loss of a valuable, operational asset after the initial investment has been paid off.

Attractiveness to Investors and Lenders: The prospect of indefinite ownership and a prolonged, stable return on investment makes BOO projects more appealing to investors and lenders who finance these large infrastructure projects. The sources explicitly state that the type of contract (BOO, BOT, etc.) is very important for attracting the necessary financing.

The project tables provided in the sources show that ACWA Power frequently uses the BOO model for many of its projects across various countries, including Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Oman, Egypt, and South Africa, which underscores its strategic preference for this structure.

Internationalization — exporting the model

What started in Saudi Arabia didn’t stay there.

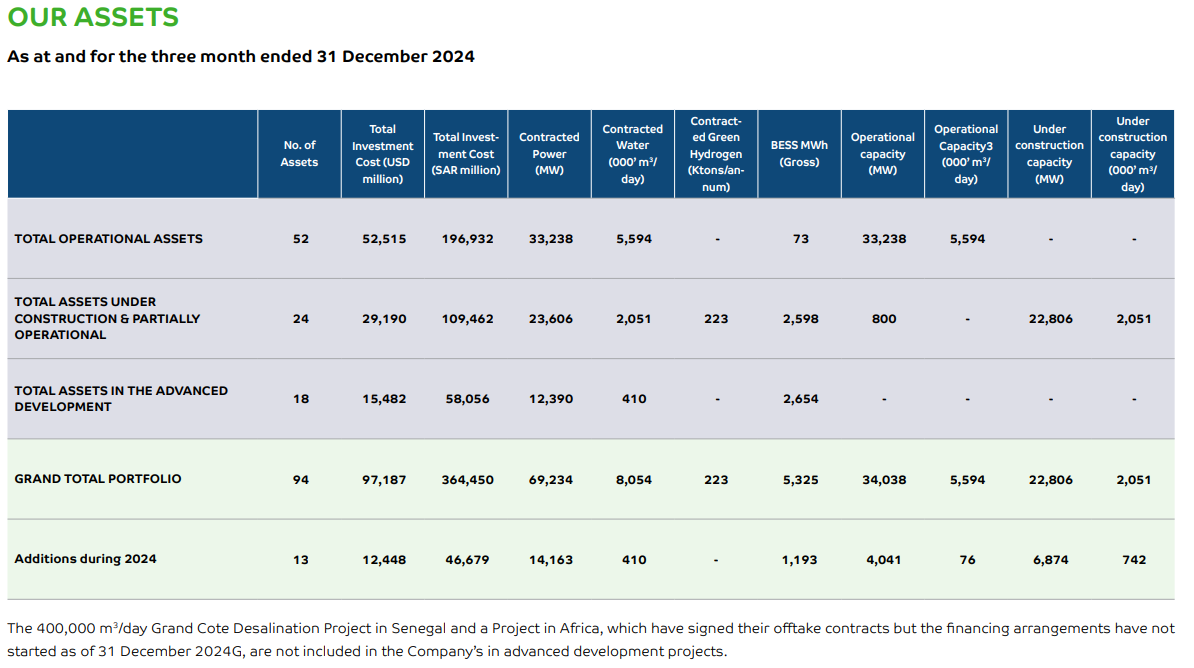

ACWA Power has exported this PPP model to more than 13 countries (for power and water), across Africa, Asia, and beyond.

An example in the bottom of the next picture, is the Grand Cote Desalination Project in Senegal (400,000 m³/day).

Although still awaiting financial close at the end of 2024, it illustrates the reach of the Saudi PPP framework into global water markets.

And what a coincidence—just this week, they announced this approach in Azerbaijan.

With 94 assets across 13 countries and ambitions to triple its portfolio by 2030, ACWA Power’s trajectory shows that PPPs are not only workable but scalable across borders.

Final thought

PPPs are about balancing roles between public and private sectors, aligning incentives, and building trust.

ACWA Power shows us how that can work in practice.

Piece by piece, case by case, we’ll continue to unpack these concepts in upcoming episodes.

Because to solve the puzzle of water, we need to understand how the pieces fit together: financing, policy, operations, and collaboration.